Ownership and motivation are key if change is to succeed. The people who will implement the changes in real life must take ownership of the changes actually happening. They are more likely to take on that responsibility if they feel some motivation for the changes. However, this is highly demanding on your communication as a manager. If you do what most people do, you risk hindering both yourself and the change.

You have just applied the finishing touches to a new strategy, and it must now be brought to life within the organisation. You call a meeting to tell your employees and colleagues about the new strategy:

“As a player in a global market, we must be agile and adaptable. We must always be ready to act under constantly changing conditions. And we must continuously take the necessary steps to keep up with developments. We are currently facing a major transition, and our new strategy is the first step in realising this transition. It will be demanding, yes, but I also dare say this: I’m looking forward to it! I believe that with the new strategy, we can continue to be a market leader. But if it is to succeed, I need you to help me.”

Still, the reaction seems absent. Apparently, the people who heard your presentation failed to see the brilliance of this new strategy. A possible – and the most likely – explanation for this is that you fell into the classic pitfall of presenting your message based around yourself and your own ambitions and goals. This is natural, but not always appropriate. When we want to create changes – large or small – it is important that we translate these changes for the recipients so that they can make sense of them and recognise how they are relevant to them. In this article, you will learn about an effective tool that can be used to motivate employees and increase their sense of ownership in relation to the changes you want to implement.

The hero model

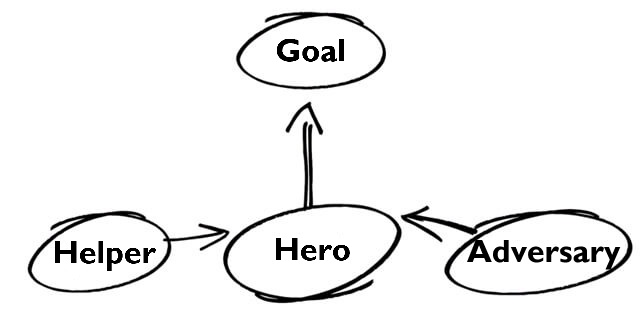

The model we will delve into now was originally developed as a tool to analyse folklore. The model (which some may know as the actantial model) assigns certain words to the different roles and relationships in a typical fairy tale: There is a hero. This hero has a goal: something he wants to achieve – usually something with a princess and half a kingdom. In order for there to be a fairy tale to tell, there must also be an adversary who initially prevents the hero from reaching his goal. If he could simply march straight into the palace and get a ‘yes’ from the princess, there would not be much excitement in the story. Furthermore, in order for the hero to eventually reach his goal and overcome what often looks like an almost invincible opponent, he must have someone there to help him. So, he has a helper.

“What does all of this folklore nonsense have to do with me and my communication?” you might think. Quite a lot actually. Not only does the model tell us something about the distribution of roles within a fairy tale. It also says something fundamental about how we, as human beings, perceive the world around us: that is, with ourselves as the focal point. We all have a number of goals we strive to achieve: an exciting career, a good family life, success at work, and so on. This also applies to your recipients. They have a variety of goals they want to achieve. And it is in light of these goals that they perceive what you say to them: How does this affect my goals? Does this help me, or does this make it more difficult for me to achieve my goals? In other words, your recipients listen to your message while thinking of how it affects them and their goals.

If you make yourself the centre of the message and ask your recipients to help you with something so that you can achieve your goal, well, then you force them to assume the role of either helper or adversary – as you have claimed the role of hero for yourself. If you are on good terms with your recipients, they might just take on the role of helper. But if you do not have a close relationship, or if your credibility is not at its peak, you run the risk that your recipients will take on the role of adversary. But then it becomes difficult for you to establish any motivation or influence recipients’ behaviour (in a way that produces positive outcomes).

The recipients are heroes

So, the model gives you three roles to work with: the hero, the helper and the adversary. And as you have probably already realised, assigning the role of hero to the recipients and that of helper to yourself is a smart thing to do if you want to make sure you earn their favour.

Assigning recipients the role of hero does not mean that you have to suck up to them, humour them or make them superstars in your presentation. It just means that they have to feel that you are talking to them, and that you have considered how what you say concerns them. In other words, you have to translate your message into their language. In the example of the new strategy, this means that you tell them what the strategy means to them. How will it affect their work or their area of the organisation? What will be different for them? And how will they notice an improvement when the strategy is implemented?

What does the hero dream about?

The more attractive a goal you can articulate, the more motivated your employees (the heroes) will be to try and achieve it. Therefore, make every effort when choosing what goal you want to articulate. Start by understanding what they dream about: what is important to them in relation to their work? Is it to develop and find smart solutions, to provide good customer service, to help users keep track of budgets or something completely different?

Once you have done your recipient analysis, the task will be to find a goal that all – or at least the majority – of recipients are likely to share. This will have the greatest impact if you can identify a goal that is relatively close to recipients’ hearts, such as succeeding with a specific project they care about or being given more time/better conditions for solving core tasks. Goals that are further from recipients’ own interests, e.g. greater growth for the whole organisation, will have a weaker impact because these will have less of a direct impact on recipients’ lives. It is also important that you choose a goal that it is credible that you can help them achieve.

Depending on who you are talking to, it will often be beneficial to talk about different goals, although you are basically presenting the same message. This does not mean you are trying to cheat the recipients, but merely that you have targeted your communication towards specific recipients.

You must be the helper

Although you must be the helper, you are allowed to talk about yourself. In fact, you should always be visible and clear in your communication so that your employees know where you stand. Letting a message speak for itself is rarely enough; your employees want to hear you set a direction and define your expectations in the clearest possible manner. The most important thing is that you should not primarily talk about goals that are important to you (or management), but instead include the recipients’ perspectives. If appropriate, you may also identify how you will help recipients achieve their goals, but you should not be the protagonist.

Use resistance wisely

Occasionally, you will probably have to announce something that from the recipients’ point of view is very difficult to put a positive spin on. This may be a change of procedures within the organisation, decided and designed by senior management to provide value in many areas of the organisation – just not for the people you are speaking to. So, what can you do to place the recipients in the role of the hero? If your message primarily results in more inconvenience for the recipients, you might want to make the new procedures the adversary and say: “I know that the new registration system is a bother, and that you’d rather spend the time getting on with your other tasks. But I will do everything I can to ensure that we do not need to register more than is necessary so that we spend minimal time on it.” Instead of trying to sell the change as something positive, you acknowledge that it involves extra burdens. But by placing yourself in the role of helper, you can try to focus on what you can actually do something about, i.e. how to handle the extra work.

At other times, the role of adversary can be filled by the concerns or objections your recipients have: Are they worried about the lack of time getting in the way of crossing the finish line? Or do they perhaps remember the last change initiative, which never really yielded the desired results? In such cases, you can help to identify any resistance and explain to the recipients how you imagine you might overcome this resistance together.

The role of helper provides credibility and ownership

Recipients are not the only people who benefit from

you placing yourself in the role of helper and them in the role of hero. If you

use the hero model in your management communication, it can also bring clear

benefits with regard to your leadership:

Firstly, it can help your employees become motivated and take ownership of the

development you want. If you place your recipients in the role of hero and

identify their goals, you create a strong “why”. You make it clear to

the recipients how what you say will affect them, and therefore why they should

do as you propose. And this “why” is particularly critical to the

employees’ motivation and willingness to take responsibility for making

something happen.

Secondly, it positively affects your credibility when you place your employees at the centre of things. That way, you show them that you want what is best for them and that you care about them. Even when you have to deliver a negative message. Conversely, it will soon affect your credibility negatively if you place yourself or management in the role of hero, as employees will become angry and frustrated that you are not focusing on anything other than your own goals.

From hero to helper

Did you feel a little bit stung by the example in the introduction? If you did, it is a sign that – as is the case with many other leaders – you have placed yourself in the role of hero and speak based on your own goals and aspirations. As the article has hopefully demonstrated, this is not appropriate. Whether your message affects the recipients positively or negatively, you have a significantly better chance of a good reception if you make sure you put your recipients in the role of hero. Let us revisit the example from the introduction – how might it look if the roles were reversed?

“Over the past year, we have all noticed how we have had to run faster to keep up. And how we constantly have to follow new rules and requirements. Of course, making changes is always demanding, but as you have probably seen, we are not entirely working in the smartest way possible. We have tried to take this into account in the new strategy. Therefore, it is my hope and firm belief that you will find everyday life a little easier and more fun once we implement the new plans. You will have more time to focus on what you do best: namely, creating first-class products for our customers.”

The next time you need to instill a sense of motivation and ownership, keep in mind the recipients’ need to meet their goals when choosing how you want to present your message. Adapt your presentation to make the recipients feel that you are talking to them and understand how your message affects their world. That way, you will be able to come closer to achieving your own goal.